Diversity Corner

Advocacy and Public Policy in the Society of Pediatric Psychology: How to Avoid History Repeating Itself

By Michael C. Roberts, Ph.D., ABPP and Anne E. Kazak, Ph.D., ABPP

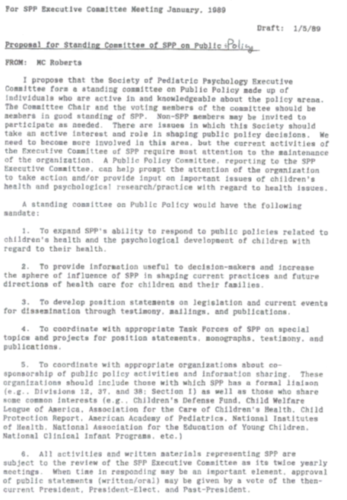

The Society of Pediatric Psychology (SPP) has had a longstanding interest, but not always action, in advocacy. The minutes of the Board of Directors and general membership meetings of SPP contain a copy of a 1989 proposal for a public policy committee (see Figure 1). The proposal was prepared by Michael Roberts, Ph.D. on behalf of the Executive Committee in 1989 when SPP was then Section 5 of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association (APA).[1] The proposal noted that “there are issues in which this Society should take an active interest and role in shaping public policy decisions” by forming an SPP Public Policy Committee to “help prompt the attention of the organization to take action and/or provide input on important issues of children’s health and psychological research/practice with regard to health issues.” This standing committee would have the mandate “to expand SPP’s ability to respond to public policies related to children’s health and the psychological development of children with regard to their health; to provide information useful to decision-makers and increase the sphere of influence of SPP in shaping current practices and future directions of health care for children and their families; to develop position statements on legislation and current events for dissemination through testimony, mailings, and publications;. . . to coordinate with appropriate organizations about co-sponsorship of public policy activities and information sharing. . .”

The proposal was approved by the Board and called for SPP to more fully engage in advocacy and policy. Notably, the society had done some advocacy to that point (e.g., a few position statements and a testimony statement approved by the SPP Executive Committee regarding the Child Victim Protection Act of 1985 (Serial No. J-99-48), but this board action was designed to be a more robust commitment by appointing an officer and forming a “standing committee.”

Meeting summaries and minutes were often published in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology (JPP) as an open source of information to the members about board activities. In searching these records, we found some mentions of this advocacy and public policy proposal after it was approved (see Figure 2). Although there was continuing endorsement by the board reflecting interest and enthusiasm, we were unable to find any evidence that SPP ever appointed a public policy officer or formed a public policy/advocacy committee, as approved by the Board. We do note that in 2005, prompted by APA, Vanessa Jensen, Psy.D. was appointed to serve as the conduit for advocacy action alerts to the SPP listserv.

Over its 53 year history SPP has made few official ventures into public policy or advocacy. Of course, many members of SPP have been active in advocacy over time for the profession, for improved services for children and families in health care, for funding for research into pediatric psychology concerns, and for social justice issues. Some pediatric psychologists as individuals have outlined advocacy and public policy positions (e.g., Armstrong, 2009). Several have written about their experiences, in the Pioneers in Pediatric Psychology series in JPP, for example, Black (2015), Johnson (2015), Magrab (2013), Roberts (2015), Wertlieb (2016), and Willis (2016). Some more recent publications also emphasize policy and advocacy. Notably, some more recent publications in Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, for instance, described advocacy positions and training activities in policy and advocacy (e.g., McCabe, Leslie, Counts, & Tynan, 2020; Morgan, 2019; Shahidullah, Kettlewell, & Green, 2019).

Pediatric psychologists are also active in the advocacy efforts of the larger APA organization as well as other professional and social advocacy groups. As just a few examples, Sharon Berry, Ph.D. currently chairs the APA Advocacy Coordinating Committee and has received awards including an APA Presidential Citation for her advocacy to improve the psychology education and improve the health of children and families; W. Douglas (“Doug”) Tynan, Ph.D. has held positions at APA, the American Diabetes Association, and now as President of the Delaware Psychological Association where he advocates for mental health for children and adolescents living with chronic illnesses; Christine Chambers, Ph.D. in Canada uses her research to inform public and institutional pain policies for children; F. Daniel (“Danny”) Armstrong, Ph.D., through his faculty and administrative positions, has engaged in advocacy at the federal, state, and local governmental levels; Vanessa K. Jensen, Psy.D. testified to her state legislature regarding discrimination against gay and lesbian individuals; Janelle L. Wagner, Ph.D., translated her research and clinical work in pediatric epilepsy to state advocacy for persons with epilepsy, And there are many others we cannot acknowledge here who have been active in advocacy and policy.[2] Even with this level of representation, there have not been many, if any, official actions or formal advocacy by SPP.

The current SPP Strategic Plan, approved at the end of 2021 after two years of development, includes a pillar devoted to advocacy (Figure 3). There are four objectives within the pillar that address an infrastructure for advocacy, training and opportunities to advance the advocacy skills of members, increased involvement in APA advocacy activities, and collaborating in partnership with key stakeholders (Society of Pediatric Psychology, 2022). This plan is congruent with prior SPP activities for moving the organization to take a larger role in advocacy and focusing on most relevant policy issues.

What lessons can be learned from this dig into the SPP records? Most notably, even good ideas such as the 1989 proposal approved by the SPP Board can get lost due to lack of follow-through, inactivity, inertia, and apathy. If the organization starts something thought to be worthwhile, there needs to be a long-lasting plan for implementation and maintenance not just an assumption it will carry forward on the basis of a good idea. Without continuing interest by people in power who will champion a cause or activity past the initial enthusiasm, even important initiatives will lose momentum and relevance. SPP has developed a number of worthwhile initiatives that once had a champion such as a president to press for initial action, but where longer-term follow-up was lacking after the presidential term. The lessons of history should inform the organization to ensure that the current effort of endorsing an advocacy pilar succeeds and maintains for the future.

Advocacy based on pediatric psychology science and practice needs to succeed and continue past the present energy and endorsement. Consequently, many members need to become involved to make sure that this is not just a fleeting effort, but one that can and will be maintained beyond current enthusiasm. Broad initiatives may suffer if activities are not coordinated or selected carefully based on their relevance to SPP with short and long-term goals. Of course, as a science-based field, advocacy requires effort at identifying, studying, and formulating appropriate policies for which to advocate, not just performative activism. Advocacy may be seen as a promise and a potential; advocacy requires follow-through to make “real” and powerful. There are many issues that are relevant and, inevitably, although hard to predict in advance, some will be more productive than others. History speaks to the importance of thinking of advocacy as a sustained program, requiring multiple champions and ensuring a continuous cadre of trained and committed pediatric psychologists as advocates for policies on which professional expertise can contribute and from which patients and their families will benefit. It is important to note that advocacy can be fulfilled through individuals pursuing their interests and involvement through specific advocacy organizations. However, where SPP as an organization would seem to make the most credible impact will be, as the 1989 proposal urged, through giving informed input on the “important issues of children’s health and psychological research/practice with regard to health issues.”

References

Armstrong, F. D. (2009). Individual and organizational collaborations: A roadmap for effective advocacy. In M. C. Roberts, & R. G. Steele (Eds.), Handbook of pediatric psychology (4th ed., pp. 774-784). Guilford.

Black, M. M. (2015). Pioneers in pediatric psychology: Integrating nutrition and child development interventions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(4), 398-405.

Brady, K. J. S., Durham, M. P., Francoeur, A., Henneberg, C., Adhia, A., Morley, D., . . . Bair-Merritt, M. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to integrating behavioral health services and pediatric primary care. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 9(4), 359-371.

Johnson, S. B. (2015). Commentary: The Wright Ross Salk award: Reflections on service with a purpose. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(10), 1008-1013.

Magrab, P. R. (2013). Pioneer in pediatric psychology: Echoing the voices of children: A journey through pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(1), 12-17.

McCabe, M. A., Leslie, L., Counts, N., & Tynan, W. D. (2020). Pediatric integrated primary care as the foundation for healthy development across the lifespan. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 8(3), 278-287.

Morgan, A. (2019). Contributing to global mental health: Can pediatric psychology extend our reach? Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(2), 157-169.

Roberts, M. C. (2015). Pioneers in Pediatric Psychology: Assisting in the developmental progress of pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(7), 633-639.

Shahidullah, J. D., Kettlewell, P. W., & Green, C. M. (2019). Training pediatric residents in behavioral health collaboration: Roles, evaluation, and advocacy for pediatric psychologists. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(2), 198-210.

Society of Pediatric Psychology (2022). Strategic Plan 2022-2026. Accessed from https://pedpsych.org/vision/ on August 17, 2022.

Wertlieb, D. (2016). Pioneers in pediatric psychology: Smashing silos and breaking boundaries. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(10), 1067-1076.

Willis, D. J. (2016). Pioneers in pediatric psychology: Helping shape a new field. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(2), 210-219.

Figure 1: 1989 Proposal for an SPP Public Policy Officer and Standing Committee

Figure 2: Excerpts of minutes from SPP Board meetings

APA Convention in New Orleans, LA, 1989, board meeting Minutes

Advisor on Public Policy: It was decided at the 1989 midyear meeting that Section 5 would financially support a Public Policy Advisor. There was lengthy discussion regarding the proposed role of such an advisor. It was decided to defer appointing an advisor at this time, but Donald Routh was asked to chair a committee to examine the potential role of such an advisor.

He was asked to make a formal report to the Board at the midyear meeting.

Midwinter Board meeting minutes, Feb, 1990

Advisor on Public Policy

At the 1989 Mid-Year Meeting, the EC voted to create a position of Advisor on Public Policy, and agreed to fund this Advisor to attend the EC Mid-Year meetings. At the August 1989 EC Meeting, Donald Routh was asked to chair a committee to examine the potential role of a Policy Advisor,

and to make a report to the EC at the 1990 Mid-Year meeting. Donald also was asked to represent Section 5 at the Year 2000 Health Objectives Consortium meeting in Washington, DC. In the intervening time, it was learned that Donald Routh is unable to continue to work on this committee, and he was unable to attend the Consortium meeting in Washington, DC. During discussion on the role of a Public Policy Advisor for the Section, Michael Roberts reviewed his original proposal for the Advisor. This person primarily would be an information source for the EC and Section membership about current legislative and policy issues, and could guide the EC in application of its task forces, etc. on public policy issues. Considerable discussion revolved around defining the responsibilities of this Advisor, such as synthesizing the major policy issues affecting children, youth, and families. It was decided to place another Call for Public Policy Advisor in the SPP Newsletter, and Jan also will place an ad in the Division 37 Child, Youth & Family Services Quarterly.

No mention in minutes of board meeting APA convention Boston August 1990

Minutes of Midwinter mtg of Board, January 1991

Public Policy Advisor

No one has expressed interest in this position to date; it was decided to defer action on this position until a later time when we might be able to recruit someone with interest and time to carry out this activity.

Figure 3: Advocacy Pillar of the 2021 SPP Strategic Plan

GOAL: BECOME A TRUSTED LEADER IN PEDIATRICS AND PEDIATRIC PSYCHOLOGY ADVOCATING FOR THE HEALTH AND WELLBEING OF CHILDREN, ADOLESCENTS, AND FAMILIES.

Objective 1: Create and maintain the infrastructure for an advocacy identity for the society.

Objective 2. Provide training and opportunities to advance the advocacy skills of members.

Objective 3: Enhance member engagement in APA advocacy efforts to ensure that Pediatric is represented.

Objective 4: Incorporate the lived experience of children, adolescents, and families in the society’s advocacy work.

Objective 5: Leverage and enhance the partnerships with pediatric organizations to ensure that pediatric psychology is represented in ongoing advocacy efforts.

1 The minutes alternate in what they call the same governing body of SPP: Board of Directors, Executive Committee, depending on the proclivities of the Secretary.

2 This enumeration is only illustrative, not comprehensive in documenting all individuals’ advocacy efforts as there are many people who have been active either intermittently or more consistently in advocacy and policy development. Although beyond the purpose of this brief article, the SPP members might find useful and interesting additional descriptions of pediatric psychology advocacy and policy activities.